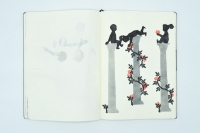

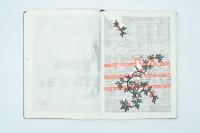

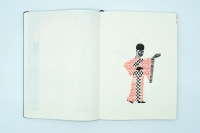

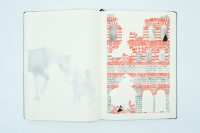

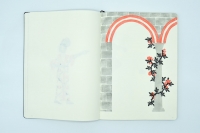

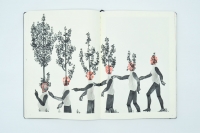

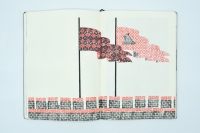

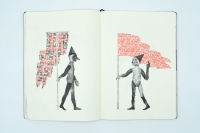

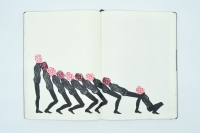

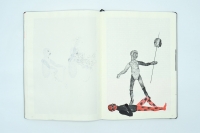

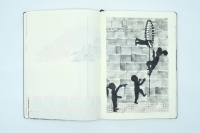

In the centuries following the semi-abandonment of Constantinople after it was sacked by the Crusaders in 1204, the city’s famed rose bushes went wild. And so, when the Ottoman troops finally breached the city walls in May 1453, the roses were in full bloom. During the gradual demise of the Byzantine Empire, thousands of manuscripts made their way from East to West, in one of many factors that fostered the Renaissance, along with the rise of moveable type and the printing press in Europe. These ideas inform the loose narrative of The Fall of Constantinople. When I began to create it, carving rubber stamps by hand out of erasers, I had recently ended a year-long stint in Beirut, and was months away from becoming a father. If the first images were more of a reflection on the cruelty of the Syrian civil war, slowly the book was conquered not only by rose vines and architecture, but also by children and pregnant women, playing, working and plotting their escape.

Prints, artist book (59 plates), interactive sculptural installation, and video (12').

The show at Galería La Caja Negra, 5-7/2024, in May-July 2024, included a series of activities: a child-friendly opening; an artist book activity for children organized alongside Christian Fernández Mirón; a perfume sampling session led by Abanuc Salesas; and a lecture on the fall of Constantinople by Byzantine historian Raúl Estangüi Gómez.